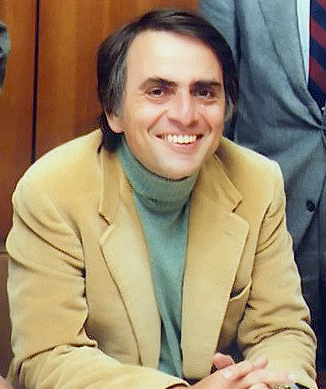

Carl Sagan

Carl Edward Sagan (/ˈseɪɡən/; November 9, 1934 – December 20, 1996) was an American astronomer, planetary scientist, cosmologist, astrophysicist, astrobiologist, author, and science communicator. His best known scientific contribution is research on extraterrestrial life, including experimental demonstration of the production of amino acids from basic chemicals by radiation. Sagan assembled the first physical messages sent into space: the Pioneer plaque and the Voyager Golden Record, universal messages that could potentially be understood by any extraterrestrial intelligence that might find them. Sagan argued the now-accepted hypothesis that the high surface temperatures of Venus can be attributed to and calculated using the greenhouse effect.[2]

Initially an associate professor at Harvard, Sagan later moved to Cornell where he would spend the majority of his career as the David Duncan Professor of Astronomy and Space Sciences. Sagan published more than 600 scientific papers and articles and was author, co-author or editor of more than 20 books.[3] He wrote many popular science books, such as The Dragons of Eden, Cosmos, Broca’s Brain and Pale Blue Dot, and narrated and co-wrote the award-winning 1980 television series Cosmos: A Personal Voyage. The most widely watched series in the history of American public television, Cosmos has been seen by at least 500 million people across 60 different countries.[4] The book Cosmos was published to accompany the series. He also wrote the 1985 science fiction novel Contact, the basis for a 1997 film of the same name. His papers, containing 595,000 items,[5] are archived at The Library of Congress.[6]

Sagan advocated scientific skeptical inquiry and the scientific method, pioneered exobiology and promoted the Search for Extra-Terrestrial Intelligence (SETI). He spent most of his career as a professor of astronomy at Cornell University, where he directed the Laboratory for Planetary Studies. Sagan and his works received numerous awards and honors, including the NASA Distinguished Public Service Medal, the National Academy of Sciences Public Welfare Medal, the Pulitzer Prize for General Non-Fiction for his book The Dragons of Eden, and, regarding Cosmos: A Personal Voyage, two Emmy Awards, the Peabody Award, and the Hugo Award. He married three times and had five children. After suffering from myelodysplasia, Sagan died of pneumonia at the age of 62, on December 20, 1996.

Carl Sagan was born in the Bensonhurst neighborhood of Brooklyn, New York on November 9, 1934.[7][8] His father, Samuel Sagan, was an immigrant garment worker from Kamianets-Podilskyi, then in the Russian Empire,[9] in today’s Ukraine. His mother, Rachel Molly Gruber, was a housewife from New York. Carl was named in honor of Rachel’s biological mother, Chaiya Clara, in Sagan’s words, “the mother she never knew”,[10] because she died while giving birth to her second child. Rachel’s father remarried to a woman named Rose. According to Carol (Carl’s sister), Rachel “never accepted Rose as her mother. She knew she wasn’t her birth mother… She was a rather rebellious child and young adult … ’emancipated woman’, we’d call her now.”[11]

The family lived in a modest apartment near the Atlantic Ocean, in Bensonhurst, a Brooklyn neighborhood. According to Sagan, they were Reform Jews, the most liberal of North American Judaism’s four main groups. Carl and his sister agreed that their father was not especially religious, but that their mother “definitely believed in God, and was active in the temple; … and served only kosher meat”.[10]:12 During the depths of the Depression, his father worked as a theater usher.

According to biographer Keay Davidson, Sagan’s “inner war” was a result of his close relationship with both of his parents, who were in many ways “opposites”. Sagan traced his later analytical urges to his mother, a woman who had been extremely poor as a child in New York City during World War I and the 1920s.[10]:2 As a young woman, she had held her own intellectual ambitions, but they were frustrated by social restrictions: her poverty, her status as a woman and a wife, and her Jewish ethnicity. Davidson notes that she therefore “worshipped her only son, Carl. He would fulfill her unfulfilled dreams.”[10]:2