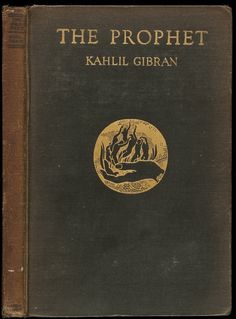

The Prophet

The Prophet is a book of 26 prose poetry fables written in English by the Lebanese-American poet and writer Kahlil Gibran.[1] It was originally published in 1923 by Alfred A. Knopf. It is Gibran’s best known work. The Prophet has been translated into over 100 different languages, making it one of the most translated books in history,[2] and it has never been out of print.[3]

The prophet, Al Mustafa, has lived in the city of Orphalese for 12 years and is about to board a ship which will carry him home. He is stopped by a group of people, with whom he discusses topics such as life and the human condition. The book is divided into chapters dealing with love, marriage, children, giving, eating and drinking, work, joy and sorrow, houses, clothes, buying and selling, crime and punishment, laws, freedom, reason and passion, pain, self-knowledge, teaching, friendship, talking, time, good and evil, prayer, pleasure, beauty, religion, and death.

The Prophet has been translated into more than 100 languages, making it one of the most translated books in history.[4] By 2012, it had sold more than nine million copies in its American edition alone since its original publication in 1923.[5]

Of an ambitious first printing of 2,000 in 1923, Knopf sold 1,159 copies. The demand for The Prophet doubled the following year—and doubled again the year after that. It was translated into French by Madeline Mason-Manheim in 1926. By the time of Gibran’s death in 1931, it had also been translated into German. Annual sales reached 12,000 in 1935, 111,000 in 1961 and 240,000 in 1965.[6] The book sold its one millionth copy in 1957.[7] At one point, The Prophet sold more than 5,000 copies a week worldwide.[6]

Though born a Maronite, Gibran was influenced not only by his own religion but also by the Bahá’í Faith, Islam, and the mysticism of the Sufis. His knowledge of Lebanon’s bloody history, with its destructive factional struggles, strengthened his belief in the fundamental unity of religions, something which his parents exemplified by welcoming people of various religions in their home.[8]:p55 Connections and parallels have also been made to William Blake’s work,[9] as well as the theological ideas of Walt Whitman and Ralph Waldo Emerson such as reincarnation and the Over-soul. Themes of influence in his work were Arabic art, European Classicism (particularly Leonardo Da Vinci) and Romanticism (Blake and Auguste Rodin), the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, and more modern symbolism and surrealism.[10]

Gibran’s strong connections to the Baháʼí Faith started around 1912. One of Gibran’s acquaintances, Juliet Thompson, reported several anecdotes relating to Gibran. She recalled Gibran had met ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, the leader of the religion, at the time of `Abdu’l-Bahá’s journeys to the West.[11][12] Gibran was unable to sleep the night before meeting him in person to draw his portrait in April 1912 on the island of Manhattan.[8]:p253 Gibran later told Thompson that in ‘Abdu’l-Bahá he had “seen the Unseen, and been filled.”[8]:p126[13] Gibran began work on The Prophet in 1912, when “he got the first motif, for his Island God,” whose “Promethean exile shall be an Island one” rather than a mountain one.[8]:p165 In 1928,[14] after the death of `Abdu’l-Bahá, at a viewing of a movie of `Abdu’l-Bahá, Gibran rose to talk and proclaimed in tears an exalted station of `Abdu’l-Bahá and left the event weeping still.[12]